The Inaccuracy of Memory - Did It Really Happen How You Think It Did?

Now, where did I put that car?

Now, where did I leave my car?

Several years ago, while working as a teacher, I was heading home one after a parents’ consultations evening. With only one class in the year group, I had finished early. For the same reason I had also arrived later than most teachers and the car park had been full, so I had parked in front of the school garage. My car was not where I had left it.

My first thought was that the janitor must have moved my car because it was in the way. I instantly knew that was impossible.

This was in the days before everyone had cell phones, so after checking around the side of the garage, through the car park and under a few stones, I headed back into the school.

The first person I met was the janitor. “You back?” he said. “I thought you were away home.”

I told him about my missing car, and he led me on another hunt around the school grounds, even though as we walked he explained that he had seen a car being driven away from where mine had been parked.

“Are you sure you left it there?” he asked as we stood scratching our heads and looking at the gap between cars.

I was pretty sure, yes, and by then I was pretty sure my car had been stolen.

I’ve used this story not to convince you that both the janitor and I are mad, but to illustrate the way minds work. We tell ourselves stories about our lives every minute of every day and the meanings we give events shape how we remember them. But those meanings aren't necessarily fixed in stone. I’m sure you’ve heard the expression, “We’ll laugh at this in years to come.” When we say this as we go through difficult events, we're reassuring ourselves that things will improve and that one day it won’t seem such a big deal.

Memory fragments

What I remember most from the night my car was stolen is a sense of watching a drama unfold, and of feeling a little detached from it all. When I went back into the school for a second time someone phoned the police – probably me but I can’t say for sure. Mostly my memories of that night are fragments: the janitor’s face as we stood in the dark, the brightly lit school corridors, the face of another teacher whose car door had been damaged, myself sitting in a little room as a passing teacher said, “I thought you’d gone home hours ago.”

Flashbulb Memories

Nobody quite knows why we remember things the way we do, though many have tried to fathom it. Back in 1977, psychologists Roger Brown and James Kulik created the term: “flashbulb memory” to describe the vivid images people often have of surprising and highly important events. If you are old enough you probably have memories of where you were when you heard the news that John Kennedy had been shot, and most of us have similar memories of where we were and what we were doing when we heard that the World Trade Center had been hit.

For several years scientists believed that these memories were more accurate than everyday memories, and the vivid images most people recall seemed to back this belief. But it turns out that even though people are generally confident they do remember these events correctly, the accuracy of these flashbulb memories is no more than of any other kind.

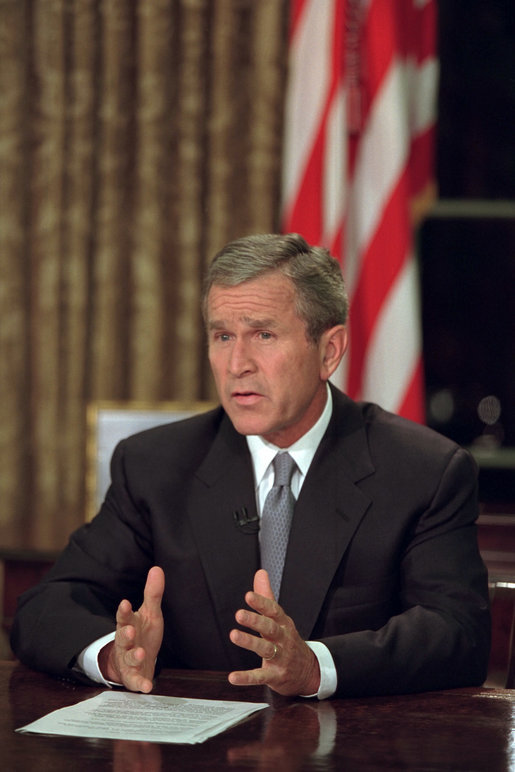

The President’s Memory

In the months following 9/11, President Bush was frequently asked how he remembered hearing the news of the attack, and on several occasions his answers were taped. These taped accounts show significant inconsistencies in his stories – which led to some people leaping to conclude that he was telling lies and that some conspiracy was at work. The reason for his inaccuracies is far simpler and more mundane: presidents’ memories are no better than anyone else’s.

The Manhattan Memory Project

Among those who saw the Twin Towers fall was neuroscientist Elizabeth Phelps. Along with colleagues John Gabrieli and William Hirst, she gathered information from 3000 participants in the week after the attack. In the study, known as The Manhattan Project, participants noted information on their personal circumstances at the time, and on their feelings. One year later and again three years after the attacks the team repeated the surveys. They found that after a year people were about 60% accurate with details, and by three years this fell to 50%. People tended to be more accurate with details of where they were than with how they felt.

The Role of Emotions in Memory

Using MRI scans the Manhattan Memory Project also found that the emotional center of the brain – the amygdala – was more active in people who had been within 4 kilometers of the 9/11 attack when they recalled the event three years on than it was in those who had been further away. From this the scientists conclude that it is possible that close personal involvement may create the necessary emotional stimulation that could be what creates the vivid memories described as flashbulb memories. The Manhattan project is still on going, checking the accuracy of memories 10 years on.

The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster

The findings of Phelps and her team are consistent with what psychologists Neisser and Harsch discovered when they interviewed people one day and three years after the Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster in 1986. One example of inaccuracy Neisser and Harsch found was that three years on more people claimed to have first heard the news of the disaster on television. Since footage of the crash was frequently shown on TV at the time, these people most likely did see it at some point, but confused the time at which that happened. This is a very common inaccuracy in memory, so much so that it has a name: the “time slice error.” We remember the events, but get muddled about when they happened, or join several memories together. (This is most likely what happened to President Bush.)

How memory works

Filling in the gaps

Returning to my own memory of the night my car was stolen: in truth I’m not actually sure if the janitor did say what I’ve written, and it was only as I went through this article a second time that I began to vaguely recall that I had said goodnight to him as I left the school building. There are aspects of the memory that appear as images in my mind and other aspects that come more as an aural memory, and then there is a sense of atmosphere, the dramatic feeling of the event. In telling the story I have filled in the gaps of memory with what I know happened but have little recollection of, or with what I think probably happened. This is exactly what scientists say creates the inaccuracies in our memories. Where there are gaps in our memories, we fill them with what we assume must have happened, and with that it seems reasonable to believe happened.

If our memories are so inaccurate…

To my mind, the implications of this are enormous. If, as the Manhattan project found, after one year we have only 60% accuracy of memory of events as significant as 9/11, then what exactly is the point in holding a grudge against people in our everyday lives? Usually we stay angry with someone because of how we think their actions made us feel, but memories of emotions are even more inaccurate than other memories, so the chances are that more often than not we are stewing over something that never existed. I’m not saying that events such as 9/11 didn’t happen: clearly it did, and clearly many people were deeply affected by it. But holding onto the feelings of distress about that or any other event will not bring back those who died, and nor will it resolve tensions. On both an individual level, and internationally there is much anger and distrust in our world. Perhaps it’s time to let go.

Of course, the way our brains are wired, that’s easier said than done. Participants in the Challenger study did not instantly change their new memories when faced with the original stories that they themselves had written down. The new “memories” remained intact. But we can choose to be willing to change, and that willingness can make a huge difference to how we see the world. Willingness starts with accepting that we don’t know everything, even about our own pasts, and it starts with questioning our beliefs that keep us locked in the behaviour patterns of fear and mistrust. In my next hub in this series I will write about a way to question beliefs that I personally have found invaluable in enabling me to let go of old fears and to live more authentically in the present.

This hub is part of a series on emotional health. If you found it useful, I recommend you read the other hubs in the series.

Further reading and references

From Scientific American: How Accurate are Memories of 9/11

New Scientist article on the Manhattan Memory Project

Daniel Greenberg’s paper: President Bush’s False ‘Flashbulb’ Memory of 9/11/01

A definition of Flashbulb Memories